Oppenheimer: technology at the service of history

Written and directed by Christopher Nolan, Oppenheimer is the most watched biopic ever at the cinema, surpassing Bohemian Rhapsody (2018) and American Sniper (2014).

Nolan said telling the story of the scientist considered one of the fathers of the atomic bomb was one of the most challenging projects ever undertaken, with many logistical and practical challenges. Among these, the interpretative key with which to narrate the events and the method of using the available technology. The merit of the success lies precisely in the combination of these two factors, where technology is at the service of the story and not vice versa as increasingly often happens with big box office blockbusters.

Oppenheimer’s plot clearly unfolds in two narrative levels which, as the director himself states, represent two realities: the first in color is the subjective reality of the protagonist while black and white is entrusted with the objective telling of the story. And, although (as the greatest historians teach us) History can never be objective, there is a precise desire on the part of the director to reconstruct the events as faithfully as possible.

Therefore, even color itself can only be a tool for the purposes of narration, where history in black and white is cold, brutal and objective, while individual and very personal reality (whose screenplay was written by Nolan himself) ) maintains color.

The two narrative levels represent a well-aware directorial choice that allows the story of man to be combined on the big screen with the actions of the scientist and to do so in an engaging and realistic way.

In the era in which technological innovation is becoming increasingly refined, the choice is to tell a story that is eighty years old but for many reasons still very current with particular effects that recall the past. Technology therefore takes a step backwards in favor of a more realistic narrative.

This is therefore why Nolan chooses an analogue process, on film. Certainly not something new: already with Dunkirk, the director had used 70mm film to narrate the landing of the Allies and reused it again for Oppenheimer. This is characterized by a 70mm wide tape: the larger size compared to the standard format (35mm) offers the director and the film superior image quality, with deeper details, richer colors and better resolution.

However, there are significant logistical challenges to address in terms of production and economics.

First, 70mm film is more expensive and requires human resources for its handling and processing. Oppenheimer is made up of 9 different reels, with a total weight of over 200 kilograms of film. Furthermore, unlike digital, film requires constant control by the operator during projection in the cinema, with careful management and a regular passage from one reel to another.

While the close-ups of Cillian Murphy’s face and the other actors undoubtedly benefit from the quality of the film, on the other hand it offers a reduced depth of field compared to smaller formats. Focusing is more complex, especially during rapid movements and with subjects in the foreground and distant background.

This type of film is also more vulnerable and subject to wear than other formats, with the risk of dust and light compromising its quality.

In the balance of pros and cons, for Nolan the aesthetics of the narrative still wins over the logistical difficulties.

In the final rendering, in fact, the sequences shot on normal 70mm film arrive in native format while the IMAX sequences, for grain-free resolution, have been optically reduced to 70mm 5-perf (5 lateral perforations per frame): with this type of processing the frame becomes wider, thanks to a photochemical process that preserves the original analog color, amplifying the details. An exceptional visual quality that is maintained even in sequences shot in black and white with IMAX film.

Nolan’s authentic approach is also reflected in the choice to make the Trinity test as real as possible, avoiding CGI.

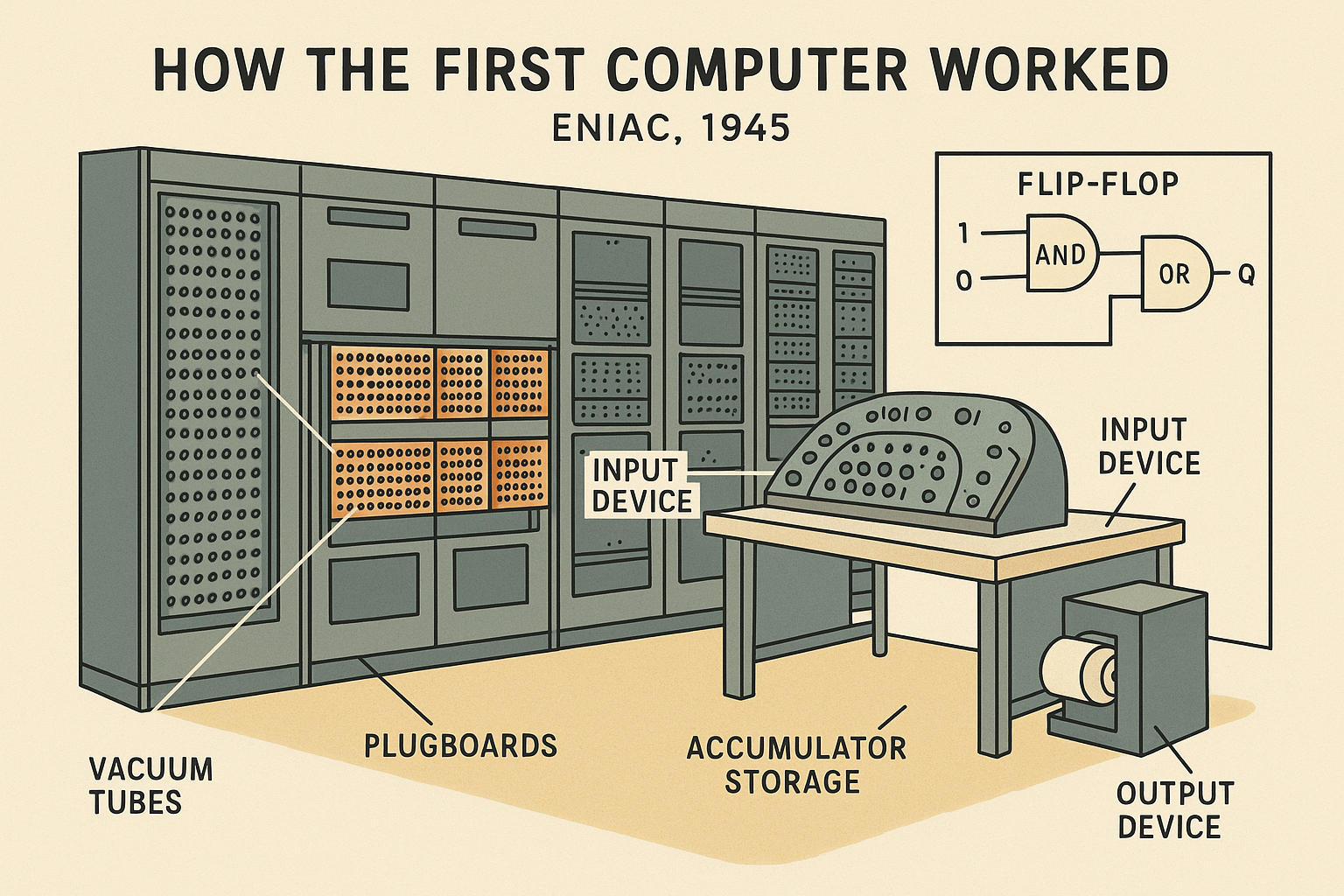

The first detonation of an atomic bomb in July 1945 in the Jornada del Muerto desert in New Mexico generated a frightening explosion with the formation of a mushroom-shaped cloud that rose into the sky.

Without CGI, Nolan and his team experimented with different types of explosives by trying different camera angles. The Trinity test was eventually recreated with a combination of TNT, gunpowder, gasoline, magnesium and aluminum powder, then placing cameras close to the explosion to make it look even more impressive. Elements such as shock waves, lighting effects, molten metal and other pyrotechnics were integrated into the final cut to make the simulated explosion realistic.

Nolan’s cinema is therefore an artisanal, nostalgic and authentic product, a return to the roots of cinematographic art that offers unique experiences for the public.